The Dark Knight of Software's Multiple Floor

As software investors continue to digest the [now obvious] public market regime change (aka mean reversion), they are increasingly debating the role software private equity (PE) firms play in establishing floor valuation multiples. In a recent piece, I explored why I believe software venture investors have effectively become forced buyers of consensus assets and, without a shift in perspectives or strategy, are at risk of eroding a few vintages of returns. I believe a similar dynamic exists in software PE, but with less clear implications for returns and more direct impacts for thinking about floor multiples.

Software-focused private equity firms, namely Thoma Bravo and Vista, serve a vigilante role in the market. When companies seem to trade at a discount or just need a break from public markets to change their tires, PE is waiting for them with (now record) pools of equity and access to debt capital. Post the “barbaric” corporate raider era of the 1980s, these contemporary (21st century) vigilantes have branded themselves as White Knights, helping struggling / cheap companies and generating excess risk-adjusted returns in the process (for 2% management fees and 20% carry, of course).

This appears to have worked incredibly well over the past 15+ years and established TB and Vista as arbiters of the software industry. However, as they’ve raised significantly more capital, adapted their strategies and now face a new market context, they begin to look more like Batman, the Dark Knight, keeping the world in check by sometimes taking one for the team (in the form of IRR). Serving a valuable purpose in keeping multiples and management honest, their multiple floor is a vital SaaS / software market input, but is also an output of AUM-driven deployment incentives that may be indicative of a returns ceiling.

Zooming out – last summer, legendary short seller Jim Chanos made an appearance on Odd Lots with Joe Weisenthal and Tracy Alloway. While the wide-ranging discussion made it clear that he saw more pain ahead in the speculative, tech-centric corners of the market (he was right), he also shared a unique and provocative perspective on the multi-trillion AUM PE buyout world:

“Think about private equity. Private equity, [has had two major winds] at their back for the last, you know, 40 years, but particularly for the last 12 years. And that is massively declining interest rates and rising equity values. And so if you are a leveraged buyer of equities, that has been a massive tailwind and what is shocking to me, and I allocate capital, I sit on some investment committees so I see the private equity numbers and I hear the pitches, what is shocking to me is that if you were buying a portfolio of stocks leveraged two or three to one, that you would expect to be doing a hell of a lot better than the S&P 500 over the past 12 years or the Russell, right? You know, even net of fees. And the fact of the matter is that's not really been the case.”

Chanos expressed concern that, with these tailwinds becoming headwinds, PE investors and their LPs may experience their own reckoning. Since then, headlines have certainly not been kind to the industry. Whether it’s Cliff Asness criticizing volatility laundering, Blackstone raising funds to offset REIT withdrawals or major banks taking losses on the Citrix financing package, the industry has not been immune from the various forms of market turmoil and negative headlines during the last year.

More importantly, Chanos’ assertion may be correct.

To anecdotally test this, I compared Vista’s returns (as of 6/30/22 as that’s all I can publicly find), against the returns of using simple leverage and buying a representative index over the last decade or so (aka the “dawn of SaaS”). Below you’ll see some basic leverage scenarios – no debt, 1x debt / equity and 2x debt / equity – used to buy various tech indices (iShares IGV, Technology Sector SPDR XLK and BVP Cloud Index) over the same periods as Vista fund vintages. I’ll let you research the details of those ETFs / indices directly, but they roughly represent broad coverage of tech and software.

While the analysis is overly simplified (e.g., impossible to time exact deployment of PE dollars, PE market-to-market is more subjective than public indices and no ability to squeeze IRR out via timing LP capital contributions), it paints a clear picture of how incorporating leverage made above-public-market returns delivered by PE less exciting than their face value during a secular bull market. I’ll also add that I somewhat discount the comparison of the 2019-vintage fund (Vista VII) as that fund has 0x DPI, meaning no capital has been returned from the fund given how recently it was raised.

Nonetheless, the biggest attack on that analysis should be that major public drawdowns can wipe out a levered portfolio (see most Tiger Cub hedge funds in 2022) whereas PE assets should be insulated given their illiquidity. That’s a hard debate to settle – especially without a counterfactual – but further from our main focus of PEs implications for growth software.

The real question is why do tech / software investors even care about software PE firms returns, fund sizes and incentives? And the answer is the expectation of a valuation floor in the assets VCs and public market investors hold near and dear - growth software.

With tech valuations having compressed the most of any asset class (Meritech Capital recently shared some astonishing peak-to-current charts), public investors have been “looking” to PE to set the multiple floor. The multiple floor is a conceptual - and occasionally actual - backstop for how low (typically on a EV/Revenue basis for minimally profitable SW companies and EV/EBITDA basis for profitable ones) companies can trade before they get scooped up. In theory, when PE buying accelerates at certain prices, public investors should be comfortable owning software stocks because they must be obviously underpriced if the PE pros are stepping in. PE doesn’t have to buy every asset to set a floor, just enough to remind everyone else they’re lurking out there.

Unfortunately, this ever-elusive floor is never obvious in real time. When Thoma Bravo bought Anaplan at 13x forward revenue in early 2022, it seemed like the floor could be in. Then, when Zendesk and the market seemed to be simultaneously capitulating and sold for 5x forward revenue in mid 2022, the floor was clearly in. Now, despite Vista recently buying Duck Creek and Thoma recently buying Coupa both around 8x forward, we’re still debating what it all means and the median software multiple still sits around 6x, near last decade lows (

). As it turns out (and as any public market investor will tell you), timing the market is a fool’s errand and every business is different.Software PE firms shouldn’t – and don’t – pitch themselves as bottom-ticking the market with precision. They became successful by understanding the differences between businesses, buying them at “reasonable prices” using leverage and then using operational expertise (aka secret playbooks) to optimize performance with an eye towards increasing profitability and cash flow. This approach should work incredibly well in software where the highly recurring revenues, low marginal cost of bits and somewhat consistent distribution patterns allow for a strong margin of safety and significant opex to optimize (cut). Capitalizing on this, firms like Thoma Bravo and Vista grew from raising ~$1B funds at the turn of the prior decade to managing $20B+ funds today.

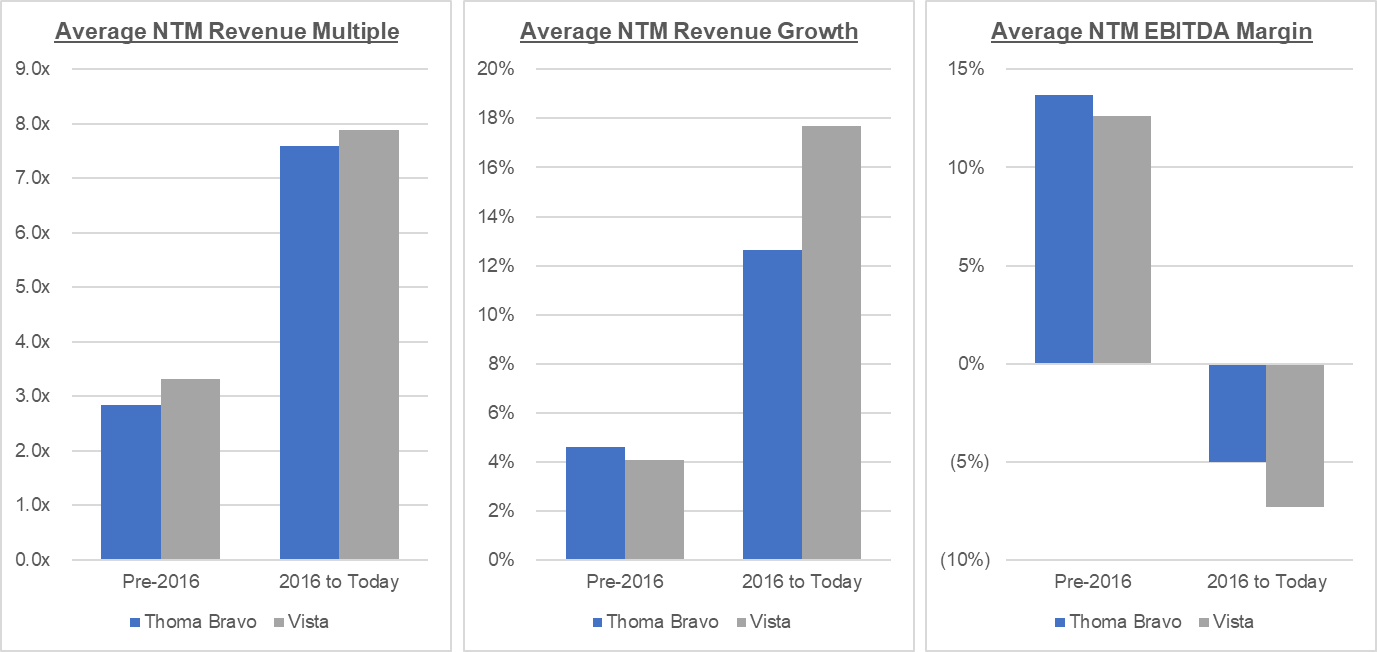

Alongside this AUM growth, there was an observable change in the strategy and profile of companies targeted by PE during this market cycle as they’ve figured out how to put increasing AUM to work. I examined the available data I could find on public software buyouts by Thoma and Vista in the post GFC era and noticed a distinct change circa 2016. As you can see below, software PE went from buying low growth (<4% rev growth) and high margin (>13% EBITDA margin) businesses at cheap multiples by today’s standards (<3x revenue, ~20x EBITDA) to buying unprofitable, growing business at multiples that we encounter more commonly in “growth SaaS” today.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact cause of this 2016 inflection point, but it was likely due to a combination of factors including:

An early 2016 SaaS crash that fazed investor faith in growth software and tanking multiples - Tableau was down ~50% on earnings and LinkedIn was down ~30% on the same day!

Software PE sitting ready to deploy their latest funds that were 6x as large as their funds from 5 years earlier

Sufficient post-GFC recovery time where the SaaS market was hitting stride and earlier mid cap SaaS / enterprise IPOs had a few years under their belt as public companies companies

A low fed funds rate <0.50% that was being carefully walked up for the first time since the great recession that still allowed for cheaper financing packages on LBOs

Regardless of the precise cause, it’s clear that the confluence of factors morphed PE in a way that will be hard to reverse. There was only so much market cap available in the low-growth, high margin software that these firms pointed their newly minted elephant guns at an incremental cohort of companies that happens to include more growth-oriented software companies. As simple as that sounds, this was a big shift in strategy. And, 7 years later, all those catalysts are even more true (with the exception of rates). SaaS has crashed, PE firms have significantly more ammo and we just witnessed a multi-year deluge of IPOs of companies that public markets are now doubting for various micro and macro reasons.

Yet it seems / seemed to be working. As this transformation of software PE played out, there were some impressive wins reinforcing its success. Thoma Bravo bought Ellie Mae in 2019 for $3.7B and sold it for $11B to ICE just 18 months later. Vista bought Marketo in May 2016 for $1.8B and sold it for $4.75B to Adobe in ~2 years for a $3B profit. The value created on these deals is larger than most venture funds and should have any investor or LP salivating. Taking out the concerns about levered beta, a consistent 15-20% IRR (see Vista slide in the appendix) is nothing to scoff at.

Now, in 2023, virtually any public mid-cap software company is fair game for PE to target. Miss a couple quarters and end up in the public investor penalty box? See your multiple contract due to growth concerns? Feel the pressure of next-gen competitors and need to make some changes out of the public eye? You might find PE on your tail. These firms scaled up and became a highly relevant “bid” for the public markets in a major way. With increasing fund sizes, Thoma, Vista and slew of others (Francisco, H&F, Permira) can now regularly buy $2B-$5B software companies and occasionally team up to approach companies as large as $10B.

In fact, they HAVE to bid these companies to deploy their capital. Where else can they go in software? This gets complicated when you realize it’s a competitive market. If firms don’t want to bid to win a given asset (at a certain price or at all), they must have a good idea of the “next-best” opportunity to deploy capital. If they don’t, they should probably just pay up a little bit to buy the company they think has a better chance of delivering an attractive future margin / growth profile. This adds a new wrinkle to the game theory of it all, where large amounts of capital chase a selected number of well-known assets with increasing scarcity.

One interesting place to see this is in a slide from Coupa’s LBO presentation. Even though it leaves out a few of the more egregious strategic multiples (mostly paid by Salesforce), it is surprising to see more sponsor activity at the higher end of the spectrum and more strategic activity at the lower end. I would expect the opposite.

Now the question becomes, what will happen when dual tailwinds of low-rates and multiple expansion reverse at the same times as PE firms are sitting on record fund sizes and playing a zero sum game? While impossible to answer a priori, it seems reasonable to expect that returns will be more challenged than the past given higher costs of capital, more forced buying and a moderated expectation of exit multiples. These factors are likely to outweigh the benefits of lower entry prices given the competitive dynamics but only time (and exit environment) will tell.

That doesn’t mean returns will be terrible and that debt can’t be refinanced if rates change or the multiple environment won’t improve dramatically down the road, but it does mean firms will be under pressures that haven’t been present in decades. PE returns ultimately come from three main sources (1) operational improvements that improve the profile of a business (2) multiple expansion as a result of the improved profile and the market [the latter over the past bull cycle] and (3) leverage on the asset to increase the juice of an equity check. PE has always been great at #1, but are now swimming against the current for #2 and #3, which makes returns more of a toss-up. Have heard anecdotally that PE firms are financing deals with all-equity (or a much higher mix of equity), if this is true, we should expect this to be a headwind to the levered returns of the past as discussed above. With LBO-affiliated debt deals offering yields from 10% (Citrix) to 12% (McAfee), it might make more sense to buy the debt instead of going for the equity upside and it’s no wonder firms like Apollo and Elliott are stepping in at a discount.

With debt becoming more expensive, it will also be interesting to see how this impacts the operational excellence playbooks developed for lower-growth companies and adapted to growthier, higher-multiple and less-profitable assets during a golden age for SW investing. As an example of this, take Coupa which is being acquired for $8B by Thoma Bravo with ~$900M of ARR, 20% FCF margins and 8% non-GAAP EBIT margins. To finance the purchase, Thoma will likely take out a loan of ~3x ARR, so $2.7B. At an 11% blended debt rate, that amounts to ~$300M in annual interest payments, representing 1/3 of Coupa’s ARR and ~4x its EBIT. At its 74% gross margin, this effectively means Coupa needs to cut almost 40% of its opex to get back to its starting FCF generation (assuming a 25% tax rate) and that’s BEFORE any operational efficiency improvements. I’m sure it can be done and math pens out – otherwise they wouldn't have bought it – but wow, that sounds painful for the company and like it may increase the risk of disrupting growth. Coupa may look like an entirely different asset on the other side of this transformation once it’s gutted. This may, in turn, impact the trading multiple - as exemplified by Informatica trading at a lower EBITDA multiple today (12x) than when it was taken private (18x).

To be intellectually honest and totally fair, the changing conditions impact the multiples and macros of the entire tech and software market. However, it takes a herculean amount of work to buy, lever-up, optimize, run and exit companies for private equity. What’s the point of all that work? If the returns aren’t superior to a levered index in a good market and good market headwinds are reversing, it may imply that ambulance chasing these companies with record capital might not be a bullet-proof strategy for alpha.

Like our friend Jimmy Chanos alludes to, PE is in a precarious position. By raising increasingly large funds on the back of 15+ years of success, PE firms are now somewhat forced and incentivized to support the proverbial multiple floor (why not make $10s of millions personally each year to deliver OK returns). Even though the market wants to think of these firms as price setters, the dynamics of deploying large funds amongst uncertainty as to when the most opportunistic deals might arise means they’re simultaneously price takers, a risky script flip.

A key output of the current setup for PE is a key input for other investors. Instead of serving as the White Knight who saves the day and gets all the glory, this asset class is evolving into the Dark Knight who saves the floor by deploying capital rain or shine. PE’s support of the multiple floor will be a boon for public software / investors and potentially a bane for their own industry. Don’t worry though, they’ll be just fine - with only 250 employees, Thoma Bravo earns ~$10M per head on its $120B AUM from management fees alone.

PE may have painted itself into a corner, albeit a profitable one. Their capital will find a home and keep things in check regardless of returns. The funds are raised, the menu of software companies for sale is well-known and everyone is eagerly looking to see where the floor is set. Alas, this also introduces an important variable to consider for public investors – PE’s presence should enter the consciousness of any public investor. If you own a software company that PE WOULDN’T chase, is it really that good of an investment or company to begin with?

If you’re a public investor, time to appreciate those keeping the market rational. If you’re a PE investor, time for the Dark Knight to rise.

Appendix: